Главная

Сфера ECM

Люди

Альбомы

Ответы мэтров

Архив

Поиск

Форум

Гостевая книга

Ссылки

Благодарности

Отзывы

Авторов!

Написать

ДЖАЗ.РУ

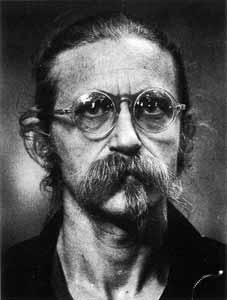

Edward Vesala Sound And Fury

"Ode To The Death Of Jazz"

|

ECM 1413 78118-21413-2

1 Sylvan Swizzle 8:34 All compositions by Edward Vesala Recorded April and May 1989, Sound and Fury Studio, Helsinki An ECM Production

ECM Records Mourning Becomes Vesala

Reports of jazz's demise have not been uncommon in the interim, often alternating seasonally with breathless accounts of jazz "revivals", and both — the bad news and the good news — have been greeted, until quite recently, with yawns, jeers, and shrugs by those who follow the music seriously. That there's a change in the air as we slink into the 1990's would be hard to deny, however. Few commentators whose surname is not Crouch would suggest we are witnesses to any Golden Age of creative music. If old notions of "progress" in the arts were suspect in their simplicity, how much more dubious is the endlessly-repeated we're-going-back-to-go-forward rhetoric of the current wave of conservative young jazz players allegedly "saving the tradition". Edward Vesala, the great Finnish drummer/composer/band-leader is weary of the double-talk. More than weary. The phone line to Helsinki crackled with his indignation (well, okay, maybe it was a bad connection)... "Jazz has become a very cynical big business. Everywhere you turn you find everything from New Orleans to swing to bebop to fusion professionally played and it has no meaning, no brain, no spirit. All of the music's human values have been washed away, it's become like something you buy at the supermarket, plastic-wrapped, with everything good pumped out of it. But people eat anything, right?" "And the groups you hear at the festivals now — and it's boom-time for festivals in Finland — they play in this completely undiscriminating kind of 'fast food' way. They misunderstand totally the potential of the music's sound and energy. From the blues to Coltrane to free improvising, this music is first of all about feeling and the transmission of feeling. This empty echoing of old styles... I think it's tragic. If that's what the jazz tradition has become then I don't see my band as part of it any longer." The "tradition", of course, has different connotations for different musicians. Lester Bowie — to reel him back in, briefly — brought this up in a conversation with journalist Paul Bradshaw. "When you're talking about tradition," he said, "it's more than a style, more than a method of playing, more than a tempo ... it's a whole life. What about the tradition of creativity, innovation, spirituality, individuality, and personality?" This "Ode", fiercely original, overflows with those qualities. Sound And Fury sounds like no other band anywhere, and right now it is on a roll, despite the twin cults of the nostalgic and the trivial that have jazz in their grip, and despite grim working prospects in Finland. According to saxophonist Jorma Tapio, the wrong people hold the positions of power in Northern jazz administration, "and the critics just run with the trends." Sound And Fury's relations with Finnish promotion agencies and media, consequently, have been troubled and turbulent. "We are not 'easy-going' people," Tapio cautions. "We say what we think." A good deal of uncompromising straight talking has led to ostracism in some quarters, and it's become harder for Vesala to tour his homeland. Not that this does much to dent the musicians' determination. If anything, they seem to draw strength from the odds stacked against them. They play all the time, virtually living in Vesala's studio (which is run by guitarist/engineer Jimi Sumen) working on the music almost every day of the year. The current band is completely committed to the drummer's vision. Outside of Sun Ra and Ornette Coleman, it's difficult to think of another contemporary bandleader who commands a comparable respect from his musicians. With an obvious pride, Edward talks of Sound And Fury members turning down lucrative session gigs, some cleaning windows to support themselves sooner than sully their chops on lesser material. He refers to the band as an extended family ("these guys are like my sons"). Others perceive the group's internal organization as a "school". Teacher and students, master and disciples. By any name, Vesala is a demanding and sometimes severe boss. He knows, very exactly, how he wants his music to sound, and won't settle for less. But his tough rehearsals are also directed to helping the musicians find their own voices. His success in this may be measured by the fact that almost all of the most striking younger players in Finland are graduates of his ensembles. "I've had guys come into the band who could read anything, whose conventional technique was on a very high level, and I've had to begin again with them. Because you have to go deeper than the notes." Stories abound of daunting Sound And Fury sessions, the leader driving the group to the limits of physical endurance. Strictly nonconformist in his drumming, Vesala will tolerate no hackneyed playing from his men, downing tools at the hint of a cliché. Though he directs the players to immerse themselves in the music of jazz's real creative forces, mere imitation is taboo. Listen to Coltrane's emotional power, he instructs, listen to the gravity of Haden's bass lines (etc.), but never copy. When working on realizations of his compositions (the "Ode" is meticulously structured throughout) his resourcefulness in putting his point across often extends to singing each man's part to him. If that fails, he'll switch instruments. "I'm a drummer, but if I have to I can play every instrument in the band... bass, trumpet, saxophone, whatever. Well enough to show what's needed." Practise sessions, Jorma Tapio explains, frequently focus on the exploration of moods, the group improvising in response to Vesala's verbal directives. Play as if playing for the first time. As if angry, insane, possessed... The process helps the players attune themselves to each other's sensibilities and find agreement in sound. "Bringing people through, getting them to understand my musical concepts is heavy work", Vesala says, "but the band now is fantastic. I feel very good about it." Tapio, with Sound And Fury for five years, notes that "before, there was a problem of musical level inside the band. People were at very different stages of development, with Edward so obviously so much better than the other players. Now the group sound is more unified than in the 'Lumi' period." Recorded in 1986, "Lumi" made its mark, however, justifiably registering in Wire magazine's listing of the most important records of the decade, and picking up critical accolades throughout Europe. I wouldn't presume to evaluate Vesala's larger ensemble records in terms of good/better/best. 1974's "Nan Madol" sounds to me as fresh and "new" as it did sixteen years ago. "Nan Madol", "Satu" (1976), "Heavy Life" (1980), "Bad Luck, Good Luck" (1983), "Lumi", and now the "Ode" — this constellation of albums reveals an organic consistency. An exploration of the expressive potential of instrumental colour is one of the fundamental concerns of each of these, examined from the broad perspectives of Vesala's background (he has played everything from old and new jazz to rock and classical avant-garde and electronic music). From his experiences he has shaped a very personal language. References to the forms he has traversed sometimes appear to be veiled allusions to the music Vesala values most highly, more often they are integrated into his own concepts of form. This remains one music, robust enough to contain a multiplicity of possibilities, rather than the eclectic's patchwork quilt — there is a difference. Emotional expressiveness, concern with differentiated colour rather than homogeneity, a profound melodic sensibility, and a fair measure of dark wit — these are the levelling factors here, the threads that link pieces as different as, say, the tense, claustrophobic composition "Sylvan Swizzle" and the sleek, erotic tango, "A Glimmer Of Sepal". Vesala hews to Ellington's view that there are but two types of music, good and bad, and rejects no idiom out of hand, but elements adopted are invariably transformed. Call the rhythms of "Infinite Express" rock-like if you wish, the fact remains that no rock drummer has ever played with this kind of sinuosity, this tough but limber, deep-toned but light, beautifully elastic groove. And listen to the way the ensemble sound, like some free-pulsative mosaic, or speeding Dub, sheers around the pneumatic snare beat of "Winds Of Sahara", with horn riffs, skittering rhythm guitar, and wildly-spattered atonal keyboard clusters glancing off the drums' central thrust. Thrilling, and only part of the story. Vesala's orchestration of "Sylvan Swizzle", "Time To Think", and "Watching For The Signal" shames most of the work done in the notoriously treacherous waters of the third stream since the 1950s. Nothing sounds forced here. The rubato saxophone on "Time", for example, shivers naturally over Edward's rustling percussion and the almost Stravinskyan chords sustained by the other horns. The piano part, played by Vesala's wife Iro Haarla, gains its strength using silence as its pendant, the notes squeezed out, sparingly, painfully. And the final rolling wave of sound seems the only possible conclusion... These three pieces, necessarily curtailing the soloists' freedom, are very lucidly ordered. They offer us a deeper glimpse of that aspect of Vesala's composing exposed on earlier, more impressionistic pieces like "The Wind". I've had occasion to listen to a lot of Finnish contemporary music recently and found nothing remotely resembling Edward's more "formal" work. His grounding in composition at the Sibelius Academy notwith-standing, he's as independent in his distance from the straight music scene as he is from the jazz club's cosiness. "I don't think I needed the Academy at all. People go there and stay for ten years. Why? If you're as talented as I am (laughs) you can just buy a book and get through all that stuff really fast, man. I could have brought in Academy-trained players to play these pieces and they wouldn't have sounded nearly as good. My system can get the players who have that spark to a really high level much faster than any of the schools. Score paper! Hah! It's good for lighting fires with!" "A Glimmer Of Sepal" will be identified by those who know "Lumi" as "Fingo II". It's a curious fact that more tangos have been written in Finland than in any other European country. Established as a popular dance form as early as 1910, the music still has a huge audience today. It has become, virtually, Finnish country music. Sound And Fury's guest accordionist Taito Vainio also plays in more-conventional tango bands and, as far as I can gather, no ironic distance to the material is intended. "Look", Edward says, "when I was growing up, a kid from the forests, I used to play in dance bands. I played tango. And my focus was always 'What's good in this form? What is there that's positive that I can get out of this situation?' I always worked towards that. Same thing later when I played heavy rock. The one-track jazz guys never could understand it — why are you playing this? — but I've always been like that." Hip to the progressive implications of the tango, the band plays the hell out of it. A final verdict from Piazzolla or Saluzzi is yet to be solicited, but this "Glimmer" sounds convincing. But what of our big theme? Programmatically, it does seem (I have to add to me, since Vesala doesn't care to be specific about this) to impinge on "What? Where? Hum Hum" (title suggesting a man scanning the horizon for jazz revivals?). The piece begins with a bluesy parade sequence, like W.C. Handy in the 5th dimension, or Mingus's stomping "Prayer For Passive Resistance", like some rousing wake, in brief. Midway through, the parade stops dead in its tracks and broken-time drumming, bass, and Tapio's singing alto conjure, at least to my ears (Vesala disagrees) the era of "The Shape Of Jazz To Come"... and that was a prophecy wide of the mark, alas. (The jazz to come was to be Kenny G, Harry Connick Jr, Windham Hill, Steps Ahead, and much robot hard-bop.) Well, the carnival resumes — what choice does it have? — but the final utterance, a fractured phrase of Iro Haarla's, hangs in the air like a question mark... Yet one doesn't come away from this work feeling pessimistic. If its origins are rooted, partly, in frustration, anger and bitterness, it seems, like the best blues, to exorcise those negative emotions in the uncrushable spirit of the playing. Sound And Fury, coming to bury jazz, can't help but celebrate the vital, life-affirming qualities that have made it, historically, so valuable. Steve Lake Этот альбом на сайте ECM Records | Другие альбомы ECM на нашем сайте Обновление: 12.12.2003 |

The late librarian Philip Larkin, author of All What Jazz?, the most hilariously off-target book ever written on the subject, was convinced that jazz had died around 1945 and that critics, ever since, had maintained a conspiracy of silence to save their jobs. Larkin's book was compiled in 1968, the same year Lester Bowie addressed the Big Question on his piece "Jazz Death". Is jazz-as-we-know-it dead? (Depends on what you know.)

The late librarian Philip Larkin, author of All What Jazz?, the most hilariously off-target book ever written on the subject, was convinced that jazz had died around 1945 and that critics, ever since, had maintained a conspiracy of silence to save their jobs. Larkin's book was compiled in 1968, the same year Lester Bowie addressed the Big Question on his piece "Jazz Death". Is jazz-as-we-know-it dead? (Depends on what you know.)